Ok, so the post title is a shameless attempt to grab a little piece of Internet. I started this post a year ago, and almost gave up on it. Rather than going for a complete list, I'm going with a running list. Now my names for cliches will not always match with the literary community. In fact, I can almost assure you that they won't. So, any English majors who read this, and aren't totally disgusted by my writing, please drop a note about what you think the correct cliche name would be. I can't promise I'll change it, but I can certainly make a note of it. .

I would also like to state that my intent here is far different from Val Kovalin's List of Most Hated Fantasy Cliches. I am not terrifically familiar with Val's work, but the intent seems to deride cliches as things that must be avoided in writing. I revere cliches. There are no bad cliches, there is only bad, lazy, and boring writing. And there is a simple solution to that. Put it down and find something else. Having now found this list, I am going to avoid copying it as a courtesy to Val's copyright, but these cliches are VERY common, and I'm going for commonality in the naming conventions. Val doesn't own the cliche, or the name of the cliche, only the list and his conceit that the cliches are a negative and profligate. Having read a bit of his list, I found it very distressing. Almost all of the "most hated" cliches are cliches that have been used phenomenally well by prominent authors. The list, seems to essentially be a collection of internet trolls on the subject of fantasy.

First, I will list them:

The Cliches:

Adventure Time Cliche

Advisor Cliche

Achilles Heel Cliche

Alignment Cliche

Ascension Cliche

Assassin Cliche

Band of Brothers Cliche

Beastman Cliche

Big Bad Cliche

Cataclysm Cliche

Chaos/Order Cliche

Chosen One Cliche

Coming of Age Cliche

Convergence Cliche

Christ/Christian Cliche

Dark Elf Cliche

Dungeons & Dragons Cliche

Diamond in the Rough Cliche

Dragon/Dragonriding Cliche

Dwarves Cliche

Going Crazy Cliche

Heroes Redemption Cliche

Elves Cliche

Evil Brother Cliche

Evil God Cliche

Fallen Woman Cliche

Femme Fatale Cliche

Hero's Redemption Cliche

Industrialization v. Nature Cliche

Innate Power Cliche

Kindness Cliche

Knight, The Cliche

Lord of the Rings (LOTR Race Cliche)

Norse Legends Cliche

Norse Peoples Cliche

Old Wizard Cliche

Play within a Play Cliche

Second Son Cliche

Shapeshifter Cliche

Sisterhood of Magic Cliche

Slave to Greatness Cliche

Sleeping Goddess Cliche

Telekinesis Cliche

Void/Abyss Cliche

Welsh Cliche

White, The/Good Cliche

World in Decline Cliche

Then I will group them:

General Literature Cliches

Achilles Heel Cliche

Advisor Cliche

Big Bad Cliche

Band of Brothers Cliche

Coming of Age Cliche

Convergence Cliche

Christ/Christian Cliche

Diamond in the Rough Cliche

Evil Brother Cliche

Fallen Woman Cliche

Femme Fatale Cliche

Going Crazy Cliche

Industrialization v. Nature Cliche

Play within a Play Cliche

Second Son Cliche

Fantasy Specific Cliches

Adventure Time Cliche

Alignment Cliche

Ascension Cliche

Assassin Cliche

Beastman Cliche

Cataclysm Cliche

Chaos/Order Cliche

Chosen One Cliche

Dark Elf Cliche

Dungeons & Dragons Cliche

Diamond in the Rough Cliche

Dragon/Dragonriding Cliche

Dwarves Cliche

Elves Cliche

Evil Brother Cliche

Evil God Cliche

Fallen Woman Cliche

Femme Fatale Cliche

Hero's Redemption Cliche

Industrialization v. Nature Cliche

Innate Power Cliche

Kindness Cliche

Knight, The Cliche

Lord of the Rings (LOTR Race Cliche)

Norse Legends Cliche

Norse Peoples Cliche

Old Wizard Cliche

Play within a Play Cliche

Second Son Cliche

Shapeshifter Cliche

Sisterhood of Magic Cliche

Slave to Greatness Cliche

Sleeping Goddess Cliche

Telekinesis Cliche

Void/Abyss Cliche

Welsh Cliche

White, The/Good Cliche

World in Decline Cliche

Now I will post a brief description of each. The reason for the duplicative nature of this list is that I intend this post as a resource for writers, reviewers and other thrill seekers. This list is simply alphabetized:

Achilles Heel Cliche: Simply put, a fatal flaw, a weakness of character that may or may not be obvious, but will despite all odds to the contrary be exploited by the author to illustrate the illustrate the concept that the Greeks knew as hamartia.

Adventure Time Cliche: An older cliche, more prominent during the advent of table top gaming. Like the Dungeons & Dragons cliche, but not focused on individual races and monsters. This cliche refers more to the style of writing as being very much the way a Dungeon Master might narrate a real table top game. Characters have turns, they swing, they miss, they swing again. It sounds stilted, but good authors can make these sorts of yarns work in their favor.

Paksenarrion followed this format.

Advisor Cliche: This cliche is a general literature cliche, common in situations where the main characters are counseled by a false friend, someone who pretends to have the MC's interest at heart, but actually seeks to push his own evil agenda. Perhaps the most famous evil Advisor is

Wormwood from LOTR, poisoning the ear of King Theoden, and in that case also literally poisoning him. Rasputin, Karl Rove, and Steve Bannon all fall into the evil advisor categories, though the ladder two served bad people as well. There are good advisors as well, in Martin's Game of Throne's the men who graduate from the Citadel, and are distributed among the Lords to administer wise counsel.

Alignment Cliche: In Dungeons and Dragons, and in hundreds of video games created on that gaming model, there is a stage in character creation when you get to choose your character's alignment. Lawful Good, Chaotic Good, Neutral Good, Neutral Evil, Chaotic Evil, and Lawful Evil. For a full list check out the list at

easydamus.com. While these cliche's are obviously tropes, they provide the gamer with a reference point for how their character reacts to new stimuli. A Chaotic Evil barbarian might see a random dwarf, and attack him immediately. Why? He's chaotic, and he's a racist bugger. This cliche is reserved for fantasy books in which those distinctions are really really obvious, D&D based fantasy is a clear example.

Ascension Cliche: The concept whereby a being evolves, grows or ascends toward a higher level. Though this concept occurs often, it has been brought to an art form in the works of

Steven Erikson, whose characters frequently ascend from mere mortal to demi-god, or greater, through actions, events, great suffering, purifications. Here is the

TVtropes definition.

Assassin Cliche: the Assassin Cliche is a type of warrior. The cliche includes the physical attributes of poisons, darts, daggers, stealth, tripwires, garrots, forced/stealth entry. It also includes the mental attributes of darkness, cold-hearted killer, loneliness, unfriendliness, watchful, distrustful, suspicious, careful, depression, and, of course, the one job the assassin will not take: the last vestige of humanity. Notable assassins include Hugh the Hand, Kalam Mekhar, Durzo Blint, Artemis Entrieri, Achmed the Snake.

Juliana Haygert has assembled some popular TV and Film assassins here. [MAKE NOTES IN COMMENTS AND I WILL ADD NAMES]

Band of Brothers Cliche: A small group, usually soldiers, who face particular massive extremity together and come to certain understandings, either of love, trust, companionship, or loyalty. The particularilty of the extremity matters. Soldiers who went through one battle, or a series of battles, are not necessarily bonded to another group, even within the same army, or the same conflict. This is a common fiction and non-fiction cliche. In fantasy I would name certain companies of the Malazan Army (Steven Erikson), as well as Glen Cook's The Black Company. In real life, I've met many soldiers who would sacrifice all bounds of commonality among people for their chosen brothers. Again,

TVTropes has an excellent entry on this cliche. Note that I did not get this name from this site, but anytime my names match up with others', I am thrilled.

Beastman Cliche: The Beastman cliche is an older fantasy cliche, a warrior, druid, barbarian, ranger type who bonds with a spirit animal, or several. S/he can command the obedience of animals, communicate with them, and in some cases even inhabit them or transform into them. Examples abound, the sorcerors of the Belgariad (David Eddings) who transform into wolves, Fitz from the Farseer Trilogy (Robin Hobb), Bran Stark with his Direwolf (George R.R. Martin). [MAKE NOTES IN COMMENTS AND I WILL ADD NAMES]. I was unable to find a direct correlation at TVtropes. Which is a good thing. There is the

Resist the Beast cliche, certainly a part of the Beastman cliche, and also the

Voluntary Shapeshifter (and

Involuntary Shapeshifter) all of which share similarities to the Beastman.

Cataclysm Cliche: This is a cliche often used to "explain" the genesis of a fantasy world from the present day. Frequently used in Sci/fi and crossover fiction. A massive earthshaking Cataclysm, sometimes man made, sometimes nature driven has destroyed much of the world's population, all of the world's culture, reshaped the entire planet. It is linked often to the World in Decline cliche. Some examples would be The Dark Tower Series (Steven King), Jordan's Wheel of Time, the DragonLance saga, various Final Fantasy videogames. The Cataclysm Cliche allows an author to immediately posit an ancient history, while allowing a sufficient break between then and the present such that s/he need only allude to past greatness in the form of ruins and ancient artifacts.

Chaos/Order Cliche: This is probably one of the most common fantasy cliches. It is a more modern substitute for good and evil, popular since it implies less morality and more "certainty," as chaos has a pretty obvious and uncontested definition. It also harkens to the D&D cliche of character alignment. The forces of chaos are generally pretty bad. This topic is worthy of a book of its own, so rather than discuss it here in full I will list some good examples. L.E. Modesitt's Saga of Recluce has the most spectacular treatment on the subject, actually giving some credence to chaos. Erikson's the Crippled God, whose powers are essentially chaotic in nature.

Chosen One Cliche: [IF ANYONE KNOWS A MORE COMMON NAME FOR THIS I WILL CHANGE

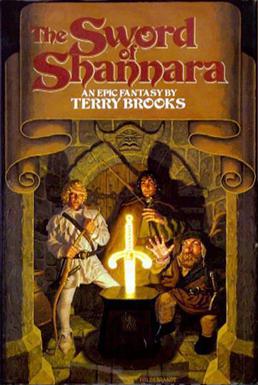

IT]. Fate has chosen this young person, either by heritage or genetics for greatness. S/he has a power, often foretold by prophecy that will allow her to defeat the evil or Big Bad. I would say 75% of all fantasy epics use this cliche. Notable exceptions are George R.R. Martin's Game of Thrones, and Erikson's Malazan epic. Some classics include Rand al'Thor (Robert Jordan), Shea Shannara (Terry Brooks), and Harry Potter. Potter's "chosenness" is up for some debate, but he is literally called the Chosen One, and fate did make him uniquely capable of defeating Lord Voldemort. The Chosen One cliche is a favorite of the teenage crowd, an homage to the idea that there is something special about "you." A comforting notion, that.

Christ/Christian Cliche: I am not one, nor am I well-versed in the large amount of symbology of Christianity. But there are a few obvious ones. Resurrection, Rebirth, Saints, Temptation, 12 apostles, the Cross, the Betrayal of Christ, the West, Water to Wine, Miracles, His Life for Yours. These are common memes in fantasy. It's one thing to use ressurrection, it's something to different to ressurrect as Aslan did in Lewis' Chronicles of Narnia. Lewis was a very religious man, his Screwtape Letters being tongue-in-cheek instruction manuals for young Christians. Tolkien and Lewis bonded over their Christianity, and indeed Gandalf's transition from the Grey into the White, as well as both Saruman's and Sauron's fall into temptation reek of Christianity. Fantasy is frequently moralistic, but modern fantasy has managed to segregate these themes from a belief in a Western style Christianity.

Coming of Age Cliche: This is a standard literature cliche. There is very little fiction that doesn't use this cliche. A young character, innocent and ignorant of the world, loses said innocence, becomes a little less ignorant. Usually this occurs through a fair amount of suffering, physical, and mental trauma. The upshot of the Coming of Age cliche is a character change that provides a vector for the story's growth, and allows fairly simple plot-based story to advance to something a little deeper. Some examples in fantasy would include Harry Potter (J.K. Rowling), Shea Shannara (Terry Brooks), the Eye of The World (Jordan), Garion (David Eddings)

Convergence Cliche: Though a convergence of fell forces is a common occurrence in fantasy, Erikson's Malazan Epic enumerated this cliche in a way that spoke openly and didactically about the nature of the tactic. Simply put, a variety of powers, strengths, armies, warriors and spell casters find themselves converging on a single event, a battle, a quest, the search for an artifact, a defense against evil. Spectacular forces are released, many are killed, everything changes and then denouement. One neat thing about Erikson's world is that it acknowledges that history is a series of convergences, not the lead up to a dramatic and final conclusion. In Terry Goodkind's

Dark Elf Cliche: A Black Elf, who instead of representing pure good, represented pure evil. It's disgusting now, as a cliche. And points to a continued and pervasive racism in common in fantasy memes. It's a legacy of the 80s, and Forgotten Realms in particular, as evil Elves in the Tolkien era were twisted by Sauron into the Orcs. Still, it's common enough to deserve mention. Dark Elves are dark skinned and white haired, but have the same delicate cast to the features, high cheekbones, narrow chins/faces, slender of regular elves. They also are magic users and frequently worship elven gods cast out of the pantheon by their godly brethren. By far the most famous is R.A. Salvatore's Drizzt Do'Urden, who rejected the evil nature of his birthright and left his subterranean habitat. Another example would be from the Marvel Verse, as enemies to Thor's Asgardian compatriots.

Diamond in the Rough Cliche: Another general literature cliche. The concept of good buried unseen in a character. Often used in tandem with the Chosen One cliche. As the Chosen One is frequently a Diamond in the Rough. However, the Diamond is a little less hackneyed, as it can be a character who is simply good, talented and hard working, rather than one fated for greatness. Though there must be many examples, I can really only think of minor characters. [HAPPY TO INSERT EXAMPLES, LEAVE IN COMMENTS]

Dragons/Dragonriding Cliche: Dragons are smart, have two to four legs, independent of two bat like wings. They range in size from that of a small dog to that of a two story house. Dragons are one of the earth's oldest myths. I won't pretend to scholarship, so here is a

list of links from the Smithsonian. One thing that is common in the cliche is that the magic inherent in dragons is that they cause immense fear/awe. They also can transform into humans. Dragonriders of Pern, DragonLance, The Hobbit, Malazan Book of the Fallen, the Magic Ship Series are all good examples of common dragon use.

Dungeons And Dragons Cliche: There is a lot to unpack with this one. It involves a plethora of different cliches, race, class, alignment cliches, heroes parties, dragon, orc, goblin, dwarf, elf, etc. It also involves a battle system and a spell system that have been reproduced in videogames, television and film. There is some dispute in the community about the genesis of D&D and the Lord of the Rings Cliche. That original versions of the D&D gaming system borrowed heavily from Tolkien is undisputed, whether the borrowing was a lack of creativity or a blatant play to attract a burgeoning fantasy market is unclear. Use the D&D cliche to evoke the LOTR cliches without the religious subtext, the One Ring to Rule Them All mythology, the age in decline cliche.

Dwarves Cliche: Solid, small, super strong, subterranean dwellers. Long beards, helmets with horns, battle axes, big noses, long-lived but not immortal. Crusty, irate, drinkers of dark brewed ale. Never the main hero, never a love interest. Have almost addictive personalities when it comes to gold and treasure. Great craftsmen, armorers and weapon smiths. Hate magic. Also, "they dug too deep" and discovered a great evil is a cliche within the dwarven cliche.

Elves Cliche: Lithe, skinny, strong, tall or short depending on the fantasy. Lovers of nature, worshipers of trees. Fantastic archers, skilled with swords. Invested with magic, beloved and symbolic of good. Skilled magic users. Great trackers, skilled at woodcraft and stealth. Lives in forest communities.

Evil Brother Cliche: the evil brother cliche is common in fantasy, but it can be seen elsewhere as well. In a medieval setting, two brothers one born to Kingship, the other merely a spare, the evil brother can frequently pair with the Second Son cliche. Also, in some works the Evil brother can be a twin, or half brother separated at birth. Some Evil brother action: the Farseer Trilogy (Hobb), Various versions of Robin Hood pitting King John against his elder brother Richard. See also the Second Son cliche.

Evil God Cliche: evil gods are a staple in fantasy fiction. Given that fantasy is frequently posed in a medieval world, it is odd that a large pantheon of gods are so prevalent, when the historical

equivalent was monotheistic. Evil Gods exist within the pantheon of gods, frequently cited as the need for balance, or a response to that which is worst in man. Frequently they begin as merely gods of vanity, fallen by arrogance into depravity. Some examples: Torak from the Belgariad (Eddings), Bane from Shadowdale (Awlinson), then Crippled God (Erikson), Shaitan from The Wheel of Time (Jordan). The problem with the evil god cliche is that even an evil god is still a god, and when evil gods start start talking, they sound a lot less godly and a lot more petty and contrived.

Fallen Woman Cliche: not a common fantasy cliche, though as the genre has grown up considerably in the last thirty years it is becoming more common. A Fallen Woman is a character, main or side, whose virtue is not merely tainted, but utterly and willfully compromised. For a genre that still uses old sexist tropes like a freeing a maiden from a dragon, or rescuing a princess from an evil witch, having a fallen woman, a woman who enjoys sex, and has it with more than one partner. Who is too cynical for love, or is so blinded by hatreds and jealousies. Expect to see the Fallen Woman more often. By far the best examples are within the Malazan epic (Erikson) Felisin and Scillara. The first, a noble woman, cute, curious, and loving, was sent to become a slave in a mining camp. She becomes a whore and a drug addict, and even after she is saved from the mines, her attitude is irreparably damaged, and she becomes a true anti-hero. Scillara on the other hand, is a whore, born of a whore, who gains freedom, finds love, and chooses to give up her child literally minutes after the baby is born. There is much to say on this topic, and it is a difficult discussion to have without resorting to sexism of any type: offensive, blatant, implicit, second-hand, micro-aggression.

Femme Fatale Cliche: A strong woman. Honestly. That said, to use more common language, a beautiful woman who uses her charm, intelligence, and sexuality to manipulate men. She can be killer, but is not necessarily a killer as much as believer in justified expedience.

Going Crazy Cliche: I have written of it before as the "Am I Going Crazy?"

cliche. In essence, the main character begins to experience things so strange and irreconcilable with reality that he begins to seriously consider the possibility of suspecting his own sanity. This is a general lit cliche, though used frequently in fantasy. Used by authors to explore the rational mind's capacity to handle that which is clearly impossible. A variant of the Going Crazy cliche is the Acting Crazy cliche, made famous by Shakespeare's Hamlet. In fantasy, this is typically used to explore character's burgeoning new skills and abilities, see Rand al'Thor of the Wheel of Time. And written about in the above link on Sanderson's Way of Kings. It also supplies a useful foil for alienating characters from their friends and family.

Hero's Redemption Cliche: This is a standard lit cliche, and a fairly obvious one. There must be a better term for it. If so, leave it below in the comments. In fantasy, it occurs fairly frequently as a general story arc, in which a benighted character finds his honor, learns to love again, makes good on a promise, etc.. This cliche taps into the concepts of deep rooted shame, and is very effective for building character motivation, as well as for shaping story arc. Think Sturm Brightblade, Rand al'Thor. This type of cliche occurs in epic fantasy more often then not. In more modern fantasy, or dark fantasy, there is frequently no, or little redemption offered (though the cliche is still operative by mere dint of expectation).

Industrialization v. Nature Cliche: A common fantasy cliche, the idea that "progress" loosely defined as an efficient means of doing things, including mass farming, factory production, munitions development and "horse-less carriages" leads to a rapid urbanization that destroys the environment, as well as destroying the rather bucolic idea of simple living. Frequently, the cliche leads to a nature "striking back" in a typical man v. nature dialectic. Sometimes this cliche is paired with the Cataclysm Cliche, it is a very moralistic take on fantasy, though as a meme it occurs quite often.

Innate Power Cliche: This might be duplicative of the Chosen One cliche. The idea however relates more specifically to the powers, attributes or magic system pertaining to the story at hand. One thing is clear, power is internal, given at birth, and though it can be shaped, trained, developed and honed: you either got it or you don't. The One Power from the Wheel of Time (Jordan) is very like this. Some people just win the genetic lottery.

Kindness Cliche: I've written often that fantasy is by nature liberal. Kindness isn't really a cliche, but it figures heavily in fantasy. Kindness is the seminal virtue of Tolkien's hobbits. They aren't tough, strong, quick, smart, or particularly nimble, but they happen to have big hearts and they see the world of Middle Earth through our eyes. Almost every single great fantasy novel of the past fifty years uses Kindness as its fundamental virtue. George R. R. Martin being an outlier, but that said, ASoIF's greatest heroes, Jaime, Tyrion, Jon, and Bran all are quite kind, though it wins them little.

Knight

Cliche: The Knight's physical attributes are obvious, full-length plate mail, shining armor, penants, chargers, lances, mustaches, beards, doublets, and sigils. He believes that what is lawful is what is right, true, and honorable, and can be quite inflexible. The knight is a militant cleric, though not a true paladin with healing powers of his own, belonging to an order steeped in a militaristic tradition with various ranks, and often believing or serving a single deity.

Lord of the Rings (LOTR Race Cliche): this cliche doubles with the Dungeons and Dragons cliche, and there is continued dispute on the provenance of such creatures as elves, dwarves, orcs, hobbits, and goblins. However, the LOTR cliche doesn't come with any of the gaming nonsense, the binding to rules of spell casting, character alignments, etc. The LOTR cliche is also tightly bound to the Dragon Cliche, the Evil God cliche, and the Christ/Christian meme. But, in a sentence, the cliche simply includes the race types common in all modern post-Tolkien fantasy, and all the cliches discussed above and below.

Norse Cliche: All modern cultures have a pre-industrial, medieval history, and it is these histories that are most often drawn upon in fantasy. The Norse cliche, is used frequently, most recently in my reviews by Joe Abercrombie in his Shattered Sea books. Think longships, oarslaves, throwing axes, men with beards, cold weather, etc. The gods of course, made popular by Marvel, Thor, Loki, and a

host of others.

Old Wizard Cliche: The precursor for the old wizards are obvious, Merlin and Gandalf. Men of mystery who are ancient, frequently living hundreds of years. Long robes with arcane symbols, funny hats, staves, long beards and pipes. There is also, in many of these Old Wizard types, a sly sense of humor, likely originating with Gandalf. Their powers depend largely on the world created for them, and more modern Old Wizards tend to have at their command much more immense powers than their older counterparts.

Play within a Play Cliche: a non fantasy cliche, used often in the genre to provide backstory. Either it's a story told around a campfire, a song, or a flashback. Also, like in Hamlet, there is sometimes an aspect that is not merely historical, but meant to shine a crooked light on the current situation.

Second Son Cliche: The Second Son cliche is a medieval favorite, but it contains a lot of variance. Historically, the first son stood to inherit, so the second son was inline to inherit some smaller portion of wealth, Or nothing at all. Of course, given the life expectancy, and the tendency for first sons to die in war, or of a variety of other reasons, second sons frequently inherited. Still, being second best, has been a meme in fantasy novels, and it creates a variety of different character types. An excellent example of both of the most prominent types, The Loyal Son, and the Wicked Son, can be found in the excellent Farseer Trilogy by Robin Hobb. The loyal son, is the one who was taught to be second fiddle to the first son, and embraced the position with great gusto. The loyal son, forced to rule, is either forced to discover new character reserves within, or to wilt beneath the pressure. The wicked son, obviously, attempts rebellion as a sop to his perpetually wounded ego. See also the Evil Brother cliche above.

Shapeshifter Cliche: This is a pretty obvious cliche. Usually part of the menagerie of a fantastic world, the shapeshifter is generally a monster that can assume various forms to employ deception. Sometimes however, it is used very effectively as a main character trait: druids who can assume the shape of some totem animal, wizards who can turn into eagles, impossibly strong alien races who can transform into dragons (Anomander pu'Rake of the Malazan Book of the Fallen). Though these are variants on the cliche, part of the basis of the cliche involves the distrust one would feel towards something that is not what it appears to be. This entails some aspect of prejudice, particularly for those who do so for deceitful or manipulative ends.

Sisterhood of Magic Cliche/The Coven Cliche: As with anything women oriented, this cliche is steeped in an ancient history of sexism that bears thinking about. Just not here. The cliche is simple, women with power gather, and those women form a society with rules, rituals, and history. Sometimes those women are witches, and are hidden, fleeing from persecution: think any book or movie about witch craft. Sometimes those women are sorceresses, and are adjudicators of law and principle, (Aes Sedai, from Wheel of Time,

Confessors from The Sword of Truth), and sometimes they are nuns (which is likely another antecedent of the cliche) such as the nuns who take King Arthur's body when he dies. In almost all cases, these cliches are steeped in a world history of sexism against women, even in worlds where they are revered.

Slave to Greatness Cliche: Like the Diamond in the Rough Cliche, this cliche relates to someone who is as nothing, who becomes great, surpassing all that stands between him/her and glory. Unlike the Diamond in the Rough Cliche, a slave is so much more downtrodden, moreover slaves, obviously have experienced such horror, ignominy, shame, backbreaking labor, and abuse, that their flowering is much more cathartic (though frequently riddled with pathos). Such characters rise above their enslaved circumstances, but frequently the scars obtained during their time of servitude is impossible to overcome. Some good examples include Raymond Feist's Magician Pug, Yarvi, from Abercrombie's

Half a King, and Kaladin, from Sanderson's

The Way of Kings.

Sleeping Goddess Cliche: The sleeping child is a very common religious theme, here's how it goes, the Earth is actually a dragon, or a titan, who settled down for a nap millions of years ago, and hasn't woken up. One day he shall wake up, and the destruction of the world is assured. I had difficulty tracing the origins of this particular myth. I had thought it was Norse because of a review I read last year, but since then I have been unable to dig it up. That said, it's existence in popular culture is very obvious. For one, Steven Erikson's Malazan epic, is based on the idea of Burn's Sleep. Burn is the being at the center of the earth, and it is she that the Crippled God has poisoned, because he wishes to destroy the world.

Transformers Prime, the cartoon, has Unicron, the Transformer God of Evil at the center of the Earth. Another good example would be the Hellfire Club of X-men renown. The Hellfire Club worship the Phoenix, who they believe has been dormant in the center of the Earth, and will wake up one day, inhabit a young hot red head and "reform" the planet. In Hayden's Rhapsody trilogy, the F'dor, the demons locked in a gravity well at the center of the Earth, want to wake up the Sleeping Child, in this case an enormous dragon. The dragon will wake up, shed the earth around it, and raze the rest. Sidebar: Googling the "sleeping child/dragon at the center of the earth' was an education on just how crazy the internet is.

Telekinesis Cliche: This cliche is misnamed, and I'm happy to change it. Another way to phrase it might be David Edding's "Will and the Word." It is a magic system where all that is needed to cast spells, and to exert magical power is will power. It includes lifting objects and throwing them, often it empowers the user to flight. Telekinesis is in direct opposition to the older and more classical view of magic, which uses spell components, arcane lore, and requires a lot of study and knowledge. Possibly the best example of telekinesis is from the cult Japanese hit, Akira. The character Tetsuo's powers of telekinesis destroys New Tokyo. In modern fantasy Telekinesis is more normal than not, examples abound.

Void/Abyss: In recent years, as Dark Fantasy has taken root, and more sophisticated notions of good and evil have become mainstream, the notion of the Void, or the Abyss has grown in use as a fantasy cliche. Evil wears many faces, but ultimately, as St. Augustine put it, "And even when men are plotting to disturb the peace, it is merely to fashion a new peace nearer to the “heart'’ desire; it is not because they dislike peace as such. It is not that they love peace less, but they love their kind of peace more." Modern fantasy has greyed the lines of good and evil so thoroughly that the new evil, is to destroy the world. Not to rule the world, not to commit acts of depravity, but to destroy it because the emptiness of the void is natural state of the universe. There are other notions of the Abyss, of course, Hell, or Hell on Earth, but even so, Hell is rather busy, full of winches, and fires, whips and grinding gears. There is also, from the

Never Ending Story, the idea of the Nothing, a billowing black mass that devours the world and everyone, good or bad, within it. Another instance might be the end game of Sanderson's Way of Kings Big Bad. The Abyss is a particular kind of bad end, because it doesn't represent greed, corruption, decay, and enslavement. It is the cold void of space, and it is terrifying. Also important to note, Nietzsche's famous quote, When you peer into the void, the void looks into you!

Welsh Cliche: The use of Welsh myths, names in fantasy. That includes Arthurian legends. Naming conventions use extra l's y's and f's in names making them generally unpronounceable to English tongues. Good examples, The Once and Future King, The Chronicles of Prydain, Elizabeth Haydon's Rhapsody Quintet

White, The/Good: The White Cliche is a term, I've stolen from Stephen King. From the wiki, "The White is the force of good that is led by Gan. The people of the White are allied together to protect the Beams and the Dark Tower from falling and stopping the world from moving on. It is the elemental force that represents wholeness, unity and health. They fight against their counterpart the Outer Dark which is led by the Crimson King." While that is all directly related to Stephen King's worlds (all of his worlds in fact) the point is clear. Good is good. It's in every fight and every fantasy. The White applies even in dark fantasy where moral ambiguity abounds. I could write pages on this cliche.

World in Decline: The World in Decline cliche is another popular sci-fi/fantasy cliche. The entire genre of post-apocalypse fiction uses the cliche as a motivating concept. In fantasy its application is used to explain why the society at hand is perpetually stuck in a non-progress loop, i.e. no technological development or liberalizing social movements. A World in Decline was once great, and shows evidence of a truly majestic, but now dead society. The current inhabitants of which dwell among the ruins. One interesting note about the World in Decline cliche is that a happy ending in a declining world does not necessarily mean that the non-progress loop can or will end. Perhaps because if it did, then it forces the recognition, both for the reader, and the author, that when they close the book and lay it down on the table, they are faced with the realities of what progress portends.

---- GODSOL, 2016

Though I did not use this list to create my own, this list of fantasy cliches is an excellent one, and should be viewed as well:

http://silverblade.silverpen.org/content/?page_id=73